Jud Yoho is a special – yet, obscure – name in Seattle history. He helped revolutionize traditional home living and kick-started a new form of consumerism from his introduction to our area of the Craftsman home.

The American Craftsman was a style of Bungalow that originated in the late 1800s by Gustav Stickley, who plied his skills as a woodworker in the Northeastern U.S. Influenced by his visits to England, Stickley imported aspects of the Arts and Crafts movement, which was a reaction – or one might say rejection – to the ornate features of Victorian home designs popular in the day.

Arts and Crafts embraced simple, sturdy, practical homes with clean lines. Stickley put his imprint on the style by seeking harmony with the natural materials and sought to use plain wood surfaces that spotlighted the grain and exposed joinery.

Stickley’s star rose after launching The Craftsman magazine in 1901 which evangelized not only his home design but the ethos of simple details amid simpler times. His magazine included architectural plans to build Craftsmans – all you needed were the materials, which could be sourced locally or through so-called kit homes from retailers Sears, Roebuck and Co., Montgomery Ward Co. and many others.

Craftsmans, one- or two-story homes (unlike the single-floor Bungalows established in the U.K.) were adopted by thousands of Americans but particularly on the West Coast. That’s where Yoho’s role as a self-made entrepreneur came to flourish in Seattle.

At 23 and following in his father’s footsteps, Yoho opened a real estate business in Seattle. He capitalized on a growing need for homes with simple features and affordable pricing to help the city’s expanding population enjoy the ideal of family life without the noisy, claustrophobic experiences endured by many in urban rentals.

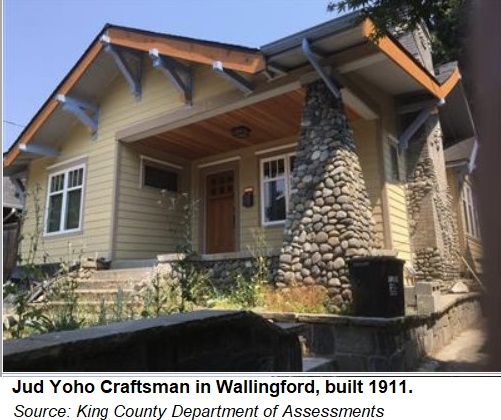

After five years of running his business, Yoho expanded into building small homes in the Wallingford neighborhood and, with two associates, he would soon incorporate the Craftsman Bungalow Co. In 1911, Yoho’s team erected a model home with a basement and hallmark front porch with overhangs at 4718 2nd Avenue Northeast and where Yoho, his wife and children would live. (Though it went through extensive renovations in 2016, the home still stands today.)

This was a time just after the successful Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition in Seattle and the Klondike Gold Rush – a period of success and industrialization for the blossoming city. A new street-car network stretched north from the city through Wallingford, Phinney and Greenwood, introducing convenient commuting from the “suburbs” to downtown and making civilized living achievable for more people.

Craftsmans were popping up within walking distance of public transportation. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer described the new-home construction “of the mushroom order … here and there and everywhere.”

Yoho was not trained in architecture nor held a degree in design, even though he would be portrayed with such skills. He was a street-smart salesman, often outwitting big-name developers by deploying modern marketing that featured engaging booklets with illustrative photos of different home styles and sparkling language that espoused suburban life. He briefly published a magazine to acquaint the wider public with what was better known on the West Coast as California Bungalows. The homes included options for built-in furniture – bookcases, sideboards and benches – as well as for reversing the exterior design and floor plan.

Using a consumer-first approach uncommon for the time, the entrepreneur promoted prefabricated homes that could be “erected by any one by following our simple directions without it being necessary to hire skilled labor,” as the marketing copy heralded.

Yoho claimed his product offered quality that matched – if not exceeded – a hand-built Craftsman. “Power driven machines can do better work at lower cost than hand labor,” the sales material read. “This has resulted in a factory equipment that does every bit of the work with the most modern machinery.”

The base price of Yoho’s specific Craftsman in Wallingford could cost buyers $1900 (roughly $60,000 in today’s money). The same company that presented the homes and design ideas also offered to finance the purchase, promoting “Easy Terms” and “same as rent” in marketing materials. The buyer would agree to make a small down payment and monthly installments to the seller, with the deed transferred to the new owner after completing payment.

This purchasing method was revolutionary in the 1910s. It introduced many buyers to the possibility of safety, independence and certainty in homeownership as consumers – mostly first-time buyers – accepted the benefits of credit in exchange for the obligation to pay off debt.

The homes were built to accept full plumbing, electricity and natural gas. They soon would be located on tree-lined paved streets, with underground sewer lines, sidewalks and off-street parking.

Yoho’s homes put Wallingford and surrounding areas on the map as a progressive suburb, creating neighborhoods of young families with a consumer-first mindset in pursuit of wealth generation associated with the American Dream. One academic recently suggested that these consumers rejected traditional norms of homeownership passed down through generations and accepted a transformative – though risky – economic driver that better suited their ideals.

That dream took a hit for many prospective buyers as the Craftsman craze dissolved when the U.S. joined the conflict in Europe in 1918 before facing a debilitating recession in 1920. This prompted Yoho to leave Seattle for Ohio, where he started a similar business. (His wife and two sons apparently stayed behind.)

We have Yoho (and many other contributors) to thank for the Seattle Craftsman. Whether built by hand or from a kit, the unassuming style of home is a major thread in this city’s colorfully quilted history.

=====

My sincere thanks to Janet D. Ore, whose research helped me present a more accurate picture of Seattle, Jud Yoho and the Craftsman. During her time as an associate professor of architectural history at Colorado State University, Ms. Ore authored The Seattle Bungalow: People and Houses 1900-1940, which is available through University of Washington Press.