In the banking system, a fundamental agreement exists. When a customer opens an account and deposits money, they trust the bank to remain open, making their money accessible for withdrawal when needed. However, history tells us that this isn’t always the case.

Throughout history, there is a long list of notable bank failures, the largest of which occurred in 2008 when Washington Mutual collapsed with $307 billion in assets. When something like this happens, it causes panic and a tremendous amount of concern over what happens with account holder’s money.

To prevent this, analysts have developed a set of metrics that act as a sort of early warning system of potential bank failures. One of the most important and widely used is the Texas Ratio. To understand how it works and why it matters, it is first essential to review, at a high level, how a bank operates.

How a Bank Makes Money

At its most fundamental level, a bank’s business model is fairly simple. Banks solicit low-cost deposits from customers in the form of checking and money market accounts, and then use these deposited funds to provide loans to other customers. Banks make money because the interest rate charged on these loans is higher than the rate paid to the depositors. The “Net Interest Margin” is a significant driver of a bank’s profitability and measures the difference between the interest earned on loans and the interest paid on deposits.

To illustrate this point, assume that a real estate developer has a checking account with a local bank that has a balance of $100,000 and an interest rate of 0.2%. At this rate, the developer would earn $200 in interest per year, assuming the balance stays the same. To complete a renovation on a new project, the same bank also provided a loan to the developer for $100,000 at an interest rate of 5.50% and with a term of 1 year. Assuming the balance stays the same throughout the year, the bank will earn $5,500 in interest on this loan.

The difference between the amount paid to acquire the deposits, 0.2% or $200, and the amount earned on the loan, 5.50% or $5,500, is 5.3% or $5,300 and represents the Net Interest Margin for this particular customer. Clearly, this is a profitable arrangement because the bank is essentially lending the customer their own money at a big margin. When banks repeat this process over and over again at scale, it can lead to a lucrative business.

But, the success of this business hinges on two basic assumptions: (1) the bank will keep enough liquidity in reserve so that when the customer needs to withdraw their funds, they can do so; and (2) the customer is a good credit risk who will make their loan payments as agreed. The Texas Ratio focuses primarily on this second assumption.

What is the Texas Ratio?

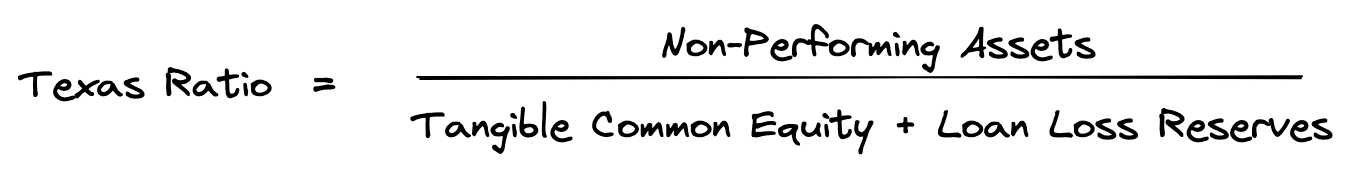

The Texas Ratio is a measure of a bank’s credit troubles. It’s calculated by dividing the bank’s total non-performing assets by its tangible common equity and loan loss reserves.

This ratio was developed as an early warning system in the 1980s to identify potential problem banks within the Texas economy, which was struggling with the collapse of the real estate and oil markets at the time.

Analysts use the Texas Ratio to forecast banks that may encounter credit-related issues—essentially, a large number of customers defaulting on their loan repayments. Gerard Cassidy and his team at RBC Capital Markets devised this ratio, finding a critical threshold: when the ratio surpasses 100% or “1”, banks are prone to failure.

The formula used to calculate the Texas Ratio is:

Non-Performing Assets are loans that are not being paid back in a timely manner. However, just because a borrower misses their loan payment does not automatically mean the loan is non-performing. In most cases, a loan will not receive this status until the principal and interest are 90+ days past due. So, in short, the numerator in this equation is the sum of the principal balance of all loans that are 90+ days past due.

The calculation of Tangible Common Equity, a measure of a bank’s physical capital, involves subtracting a bank’s intangible assets (such as Goodwill) and Preferred Equity from the bank’s book value. Loan Loss Reserves represents money banks set aside proactively, preparing for the possibility of non-performing loans moving into default. You can think of Loan Loss Reserves as money reserved for anticipated future losses.

So, the intent of the Texas Ratio is to see if a bank has enough equity and money set aside to cover any loans that go bad. Or, put another way, does a bank have enough money to absorb potential loan losses while continuing to meet their other deposit obligations.

Ultimately, one way that a bank can fail is that they make too many bad loans and don’t have enough money to cover the losses. As was the case with Washington Mutual, if this happens, it can cause depositors to lose faith in the bank and withdraw their funds en masse in a “run on the bank.” When the money runs out, the bank collapses.

Texas Ratio Calculation Example

To really drive home this point, let’s look at an example of two banks on opposite ends of the risk spectrum. The data used to calculate the Texas Ratio is publicly available through each bank’s call report and can be found on the FFIEC Website (NOTE: The example below describes two actual banks, but their names have been withheld for privacy reasons. In addition, the example is for educational purposes only).

Bank 1 is an online, savings-focused financial institution that has a limited number of banking products available to their customers. On the deposit side, it offers Savings Accounts and Certificates of Deposit, and it offers residential mortgages and commercial loans on the lending side. In their June 2020 Call Report that was filed with the FFIEC, they reported $918M in non-performing loans (Schedule RC-N), Tangible Common Equity of $145MM (Schedule RC) and Loan Loss Reserves of $14.3MM (Schedule RC).

Bank 2 is a traditional retail bank with 13 locations across Illinois. On the deposit side, they offer checking and savings accounts and, on the loan side, they offer traditional lending products from personal loans to consumer mortgages. In their June 2020 Call Report that was filed with the FFIEC, they reported $25.5MM in non-performing loans (Schedule RC-N), Tangible Common Equity of $30.4MM (Schedule RC), and Loan Loss Reserves of $10.8MM (Schedule RC).

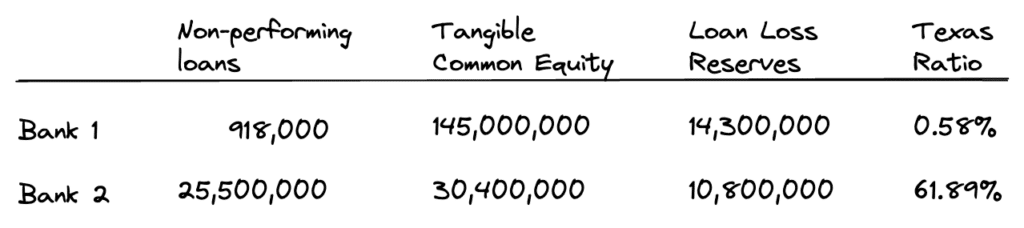

To see how the Texas Ratio shakes out for each bank, the following table provides a side by side comparison:

Granted, these two banks were cherry-picked to demonstrate a key point: that banks have distinct risk profiles. Another way to look at the table above is that Bank 1 has $918M in non-performing loans that they could eventually have to take a loss on. However, they also have $159MM available to cover those potential losses. Even if all the loans default, they have plenty of money to absorb the losses.

Bank 2 presents a contrasting scenario. With $25.5MM in non-performing loans and a mere $41MM set aside as a buffer, two critical facts emerge about this institution: (1) It has made some bad loans and is grappling with the fallout; and (2) The reserves allocated to cushion potential losses are considerably insufficient. If all these loans were to default, it could plunge the bank into a significant financial crisis.

Keep in mind that when the Texas Ratio exceeds 100% it is correlated with bank failure. However, Bank 2 has not reached this point yet. To improve their Texas Ratio, Bank 2 will have to pay closer attention to the credit quality of the loans they originate and contribute more money to their loan loss reserve account. Unfortunately, many banks are reluctant to do this as these funds come directly from income and can result in an operating loss, which shareholders do not always appreciate.

Why Does the Texas Ratio Matter?

We have established that the Texas Ratio is a predictor of potential bank failure, but how does this relate to real estate development and operation?

First, for banks that continue to invest in their branch network, they could be a tenant in a commercial office or shopping center. If a property owner is considering leasing space to a bank, the owner would be wise to review the Texas Ratio for the potential tenant as an indicator of financial strength.

Two, commercial property developers tend to carry large deposit balances in their checking accounts. As such, to prevent losses on deposits, it is wise to review the Texas Ratio for the bank holding them. In the event of a collapse, FDIC insurance only covers balances up to a certain amount. Above that, the funds could be at risk.

Conclusion

In this article, we discussed the Texas Ratio. We defined the Texas Ratio, walked through the components of the formula itself, and then we covered a detailed example of how to use the Texas Ratio to evaluate the financial strength of two banks. In our Texas Ratio example, we found the publicly available call reports for two different banks and calculated the Texas Ratio for each bank.

Our analysis showed the Texas Ratio can give a quick indication of the financial strength of a banking institution. It also indicated that the Texas Ratio can vary widely between banks. Finally, we talked about two ways real estate developers and owners can use the Texas Ratio. This ratio can be an important factor when evaluating the strength of potential bank tenants, as well as when evaluating which banks to begin or continue a deposit relationship with.